BLUE LIGHT CARD DISCOUNTS available across all therapies and packages. Thank you NHS.

Allergy vs Intolerance- Debating the Difference

Read Time 15 mins

In the realm of dietary restrictions and health concerns, allergies and intolerances often take centre stage. Shaping the way individuals approach their food choices and daily lives. With a range of overlapping symptoms, all of which can ruin your plans and positive vibes, finding out the difference between an allergy, intolerance and sensitivity often makes for exasperating reading. With societal and scientific definitions of adverse food reactions differing, terminology sometimes used interchangeably, and explanations at times varying across personalities and practices within the healthcare field.

As immune diseases and adverse food reactions now rank amongst the fastest growing chronic conditions, and ultimately now increasingly common, chances are you or someone you know has experienced some degree of itching, skin rash, sneezing, wheezing, headache, pain, nausea, bloating, brain fog, mood changes, diarrhoea, or another reoccurring symptom, in the aftermath of what should have been a non-eventful and enjoyable meal.

Whilst terms are frequently used interchangeably, they do represent distinct physiological responses with unique implications for overall well-being. Understanding the differences is not only essential for personal health management but also crucial for fostering empathy and support within these communities and the wider world, as well as ensuring accurate data and improving research.

So, let’s try and get some clarity. It’s important to get the right assessment as information is the vital first step in helping understand your triggers, know your options, navigate successfully through your quest for better health, and avert the potential of increasing anxiety around food.

In this post, I’ll do my best to unravel and explain the complexities of allergies and intolerances. Exploring their underlying mechanisms and common triggers of adverse food reactions, analysing them in the wider context of the immune system, and offering practical strategies for investigating and navigating these dietary challenges.

THE RISE IN ADVERSE FOOD REACTIONS

Adverse reactions to the environments and foods around us is a modern epidemic, with hundreds of millions of people suffering from allergies, sensitivities and intolerances worldwide. More of the population has food allergies than ever before, with rigorous surveys of food allergy prevalence indicating- at least in westernised countries- a movement towards greater persistence of childhood food allergies and higher rates of adult-onset cases than previously appreciated.

We have seen a significant rise observed in anaphylaxis cases around the globe. A comprehensive review of hospital admissions data from various regions including the U.S, Australia and Europe revealed alarming trends. With England alone seeing a 72% rise in the number of emergency admissions between 2013 and 2019. In the last few decades, the incident of peanut allergies has skyrocketed by over 300%. Coeliac disease has seen a staggering increase of over 500%.

Moreover, it’s not just the frequency of these allergies that’s on the rise; the variety of foods triggering allergic reactions is also expanding. On a similar trajectory, alongside the surge in allergic reactions, there has been a notable increase in the prevalence of intolerances and sensitivities to certain food and common dietary substances.

As the incidence of both allergies and intolerances continues to climb, there is a pressing need for heightened awareness, research, and support to address the diverse spectrum of adverse reactions to food within our communities. As well as an urgent call to rethink the various chemical, environmental and food manufacturing elements of modern living that are so clearly driving the trend.

WHAT CAUSES ADVERSE FOOD REACTIONS?

Our immune system plays a crucial role in protecting our body against pathogens, but sometimes there is an exaggerated, unnecessary response to a threat that poses no problem.

This mistaken response is triggered by the interaction of the immune system with an antigen (the allergen). An antigen is any molecule and foreign particulate matter that can bind to certain cells in the immune system, potentially provoking an immune response. Body tissues and cells have antigens, allowing for recognition and communication within our systems. Antigens can also include toxins, chemicals, bacteria, viruses, or other substances that come from outside the body. People who suffer from hay fever are well versed with the antigen pollen, people who suffer rhinitis in the autumn will be familiar with mould antigens. This post naturally centres around the antigens that exist within foods. There are also antigens that exists in the environment, notably in plants, that can cause cross reactivity with foods, eliciting an immune response once the food is ingested. More on that later.

ALLERGY, FOOD SENSITIVITY OR INTOLERANCE- what’s the difference?

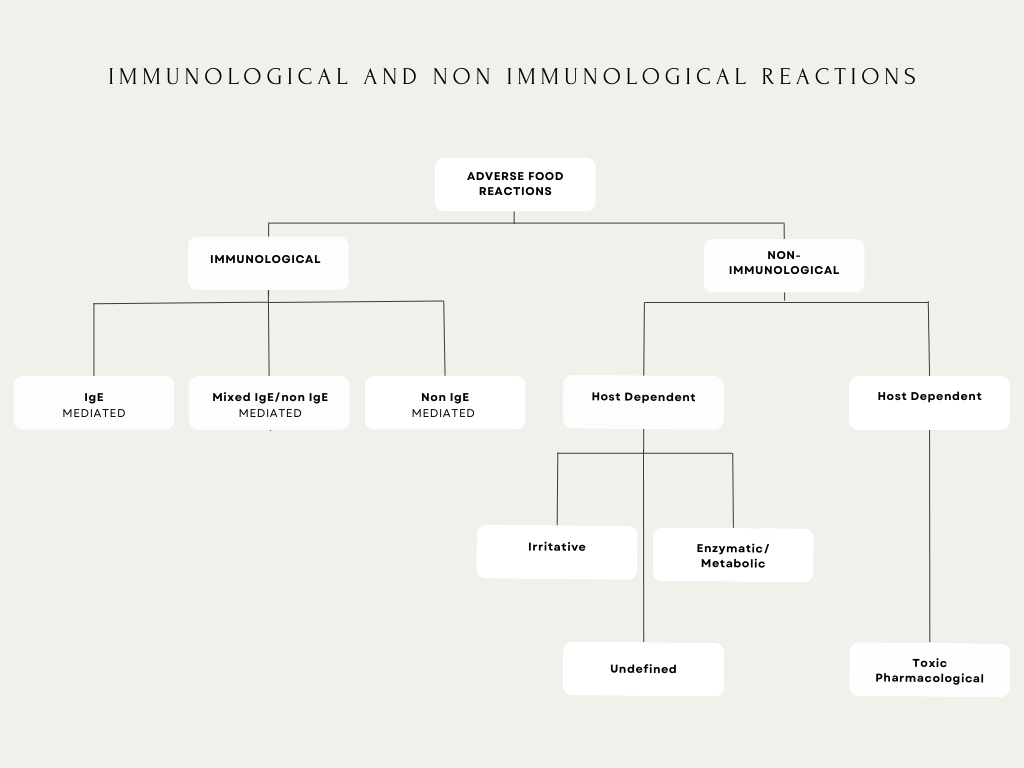

An adverse food reaction is any abnormal response to an ingested food, regardless of the exact cause, consequence or collateral connection it may have within the body. The term allergy was coined in 1906 by the Austrian paediatrician Clemens von Pirquet. Since that time, the terminology has evolved into immunological and non-immunological descriptions of adverse reactions to food.

Gargano D, Appanna R, Santonicola A, et al. Food Allergy and Intolerance: A Narrative Review on Nutritional Concerns. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1638. Published 2021 May 13

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8152468/

Immunological reactions refer to the reactions that take place where there is an antibody and/or cell related response from the immune system. These reactions to food can be classified depending on the involvement of IgE-mediated and/or other immune responses to ingested antigens. Non-immunological reactions refer to factors like metabolic disorders such as enzyme deficiencies that result in issues digesting lactose or jitters after coffee consumption.

IMMUNOLOGICAL FOOD REACTIONS AND MECHANISMS

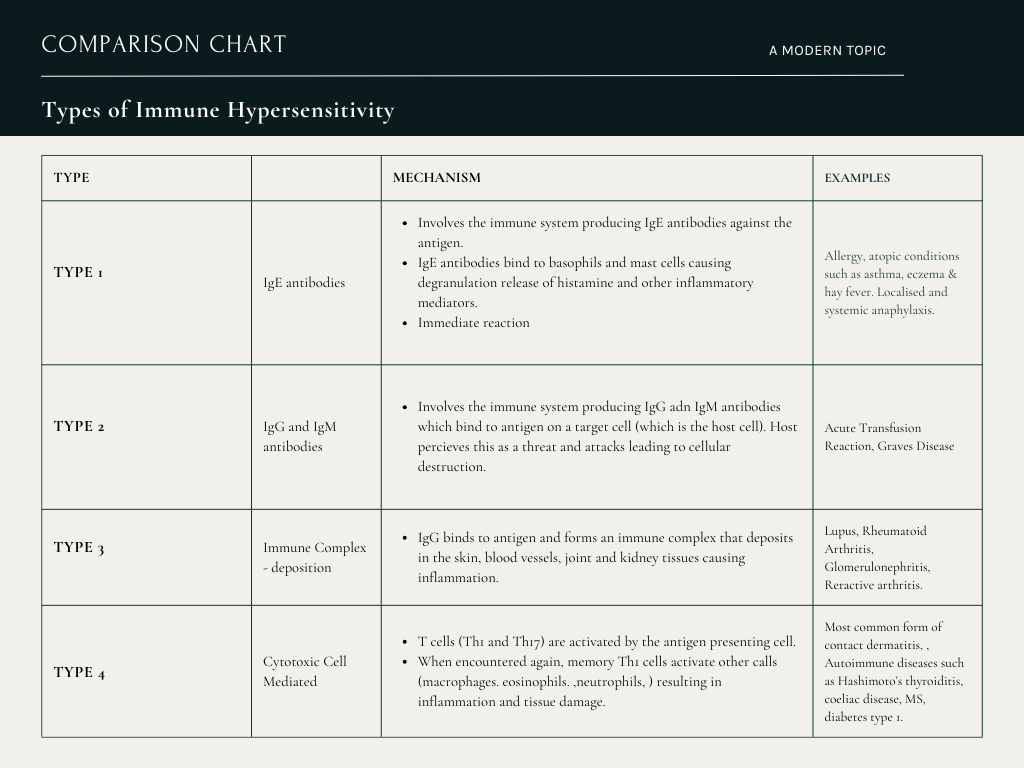

There are four traditional classifications for hypersensitivity reactions- Type I, Type II, Type III, and Type IV reactions. Some evidence suggests a potential fifth type, but this may actually be a subset of Type 2 hypersensitivity reactions.

IgE mediated reactions, or Type 1 hypersensitivities are the classic presentation of allergy. Referred to often as a ‘true allergy, they produce a positive IgE antibody test result with the immune system and involve a rapid onset of symptoms that occur soon after ingestion of the offending food antigens.

Despite this quick and immediate reaction, a second phase known as the late-stage reaction can occur 4-12 hours later, and last a further 72. There are two stages to Type 1 hypersensitivity: the sensitisation stage and the effect stage. During the sensitisation stage, the person encounters the antigen but does not experience any symptoms. During the effect stage, the person has exposure to the antigen again. As the body now recognizes the antigen, it is able to produce a response that results in the symptoms that people typically experience with an allergic reaction. Type I hypersensitivities include atopic diseases -which are an exaggerated IgE mediated immune response – such as asthma, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, and dermatitis and allergic diseases such as anaphylaxis, urticaria, angioedema, food, and drug allergies.

Non IgE mediated food reactions are classified as negative IgE test results when positively challenged in a testing capacity. Symptoms can be present, and similar (excluding the life-threatening anaphylaxis) to IgE symptoms the offending foods. In regard to biology and documentation, food specific, no- IgE mediated reactions are currently not as well understood.

Similar to Type 1, Type 2 also involve antibodies. The difference between them lies in the form of antigens that generate a response. Type 2 hypersensitivity causes cytotoxic reactions, meaning that healthy cells die as they respond to the antigens. This can cause long-term damage to cells and tissues, resulting in conditions centred around autoimmunity as individual body cells are destroyed.

In Type 3 hypersensitivity, antigens and antibodies form complexes in the skin, blood vessels, joints, and kidney tissues. These complexes cause a series of reactions that lead to tissue damage.

Unlike the others, Type 4 hypersensitivity reactions are cell mediated. Instead of antibodies, white blood cells called T cells control these reactions. They can be further subdivided into Type 4a, Type 4b, Type 4c, and Type 4d based on the type of T cell involved and the reaction it produces but let’s not fry our brains too much. This type differs from the other three in that it causes a delayed reaction, with symptom onset typically 48-72 hours later.

ADDRESSING THE CONFUSING SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NON-IMMUNOLOGICAL INTOLERANCES AND NON- IMMUNOLOGICAL SENSITIVITIES.

Addressing the confusing similarities between non-immunological intolerances and sensitivities requires further nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms and manifestations at play. While both conditions lead to adverse reactions to certain foods or substances, they do differ once more in their root causes and physiological processes.

Non-immunological intolerances typically arise from difficulties in digesting specific components of food, such as lactose or gluten. For example, lactose intolerance results from a deficiency in the enzyme lactase, which is responsible for breaking down lactose, the sugar found in dairy products. And gluten intolerance, often referred to as non-celiac gluten sensitivity, involves adverse reactions to gluten-containing foods without the autoimmune response seen in celiac disease.

Non-immunological sensitivities encompass a broader range of reactions, often characterized by heightened sensitivity to certain substances, additives, or environmental factors. Common examples include histamine intolerance, where the body has difficulty metabolising histamine-rich foods, and salicylate sensitivity, which involves adverse reactions to foods containing high levels of salicylates, natural compounds found in various fruits, vegetables, and spices.

SYMPTOMS OF ADVERSE FOOD REACTIONS

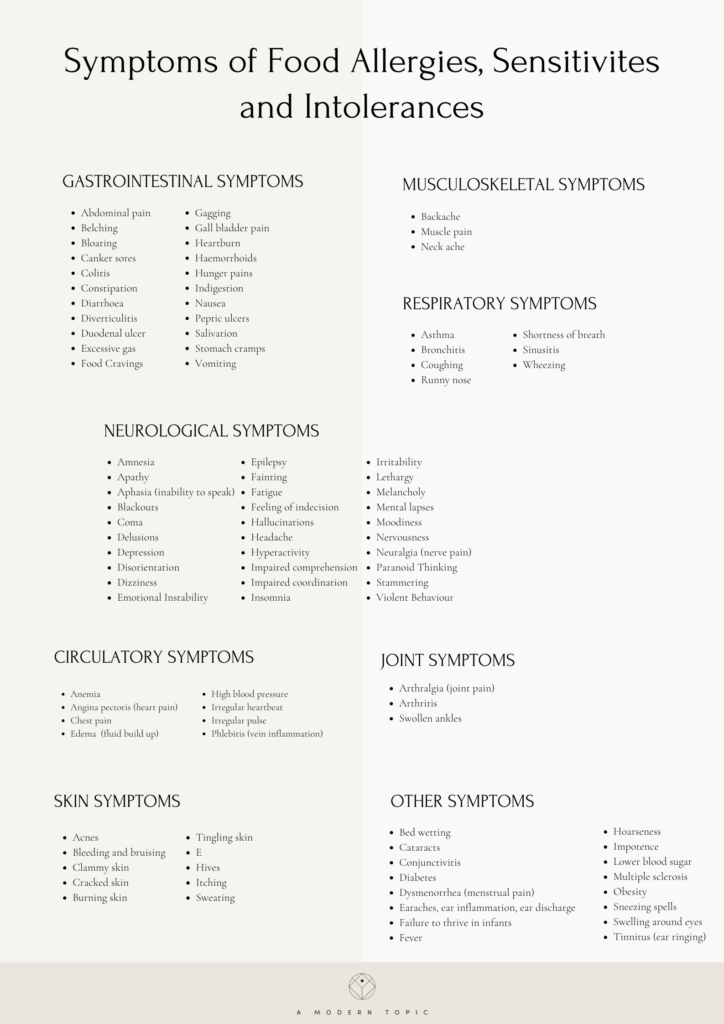

There is a high degree of commonalities in symptoms of sensitivity, allergy and intolerance despite the differences in underlying mechanisms. All can affect quality of life but the variation, seriousness and target system often dictating different approaches for management.

Ultimately symptoms of food reactions can be as diverse as we are, occurring across multiple systems in the body. It can often be difficult to tell the difference mechanisms underpinning them because at a symptom level the manifestations of food reactions- sensitivity, intolerance or allergy – often show up in similar ways, regardless of their technical and scientific classification. A key indication- before testing is able to provide confirmation- is the speed and severity of symptom onset, with IgE mediated issues occurring soon after ingestion with the potential of escalation to anaphylaxis a risk. The other antibody driven reactions, whilst occurring slightly slower, show up within hours, leaving type 4 cell mediated reaction to kick into action up to days later.

I’ve heard it mistakenly mentioned on many occasions that intolerances often only cause gut related issues. My own personal symptoms and clinical experience, along with plenty of research and the clinics of colleagues, shows otherwise. Whilst many symptoms are gut related and the reaction naturally begins in the gut, immune cells exist throughout the body, with bi directional relationships between this area and wider systems such as nervous and endocrine intrinsically linked. Thus the manifestation of illness resulting from intolerances naturally follows suit.

COMMON AND LESS COMMON ALLERGIES

Whilst a person can be allergic to any type of food, only nine foods account for most of food allergic reactions.

- Milk: Cow’s milk allergy is the most common food allergy in infants and young children. Even though most children eventually outgrow their allergy to milk, milk allergy is also among the most common food allergies in adults.

- Egg: Whilst most eventually outgrow this allergy, for some it will remain throughout their lives. Most allergenic proteins are found in the egg white, however those with allergies are advised to avoid both the whites and the yolks.

- Peanut: Peanut allergy is again very prevalent amongst children, and the third most common allergy in adults. Usually a lifelong condition, some children do outgrow it. Different to tree nuts- with peanuts growing underground-it is part of the legume family. Whilst there is a crossover with many proving allergic to both peanuts and tree nuts, it is important to know that a peanut allergy does not give you a greater chance of being allergic to other legumes.

- Soy: Another member of the legume family. More common in babies and young children, most outgrow this allergy though for some it will remain in adulthood. Individuals with soy allergy have been shown to more likely be allergic or sensitised to other major allergens including peanuts, tree nuts, egg, milk and sesame than to other legumes such as beans, peas and lentils.

- Wheat: More common in children than adults, more than 2/3 will have outgrown this allergy by the time they are 12. An allergy to wheat is not the same as coeliac disease, one is an IgE reaction and the latter is autoimmune.

- Treenut: The six tree nut allergies most commonly reported by children and adults are allergies to walnut, almond, hazelnut, pecan, cashew and pistachio. Approximately 50% of children that are allergic to one tree nut are allergic to another tree nut.

- Shellfish: This allergy is usually lifelong with about 60% of people with shellfish allergy experiencing their first reaction as an adult. Out of the two groups of shellfish: crustacean (think shrimp, crab and lobster) and molluscs (clams, mussels, oyster and scallops), crustaceans cause the most shellfish reactions, and these tend to be severe . Finned fish and shellfish are not related and having an allergy to one does not mean that you need to avoid both.

- Fish: Again, usually lifelong, and experienced predominantly for the first time in adulthood, salmon, tuna and halibut are the most common.

- Sesame: This flowering plant that produces edible seeds has been reported as an allergy that has increased significantly in the last two decades, only being officially listed as a major allergen in recent years.

Whilst far from complete, the list below gives an overview of some less common allergy foods.

- Corn : Allergic reactions to corn are very rare, but reactions can occur. Reactions can result from both raw and cooked corn.

- Meat : Allergies to meats, such as beef, chicken, mutton or pork, are also rare. An allergy to one type of meat may necessitate the need to avoid other types. allergy to mammalian meat experience allergic symptoms 3 to 6 hours after ingesting beef, pork or lamb. This type of meat allergy has been attributed to a type of sugar in meat called “Alpha-Gal.” This allergy has been traced to having had tick bites. If you have a cow’s milk allergy, you may wonder if you need to avoid beef. Or if you have an egg allergy, you may debate an allergy to poultry. Whilst studies have shown some children with milk allergy do react to beef, proper testing to confirm is essential. Heating and cooking meat can make the product less likely to cause a reaction.

- Gelatine : Gelatine is a protein that forms when an animal’s skin or connective tissue is boiled. Although rare, allergic reactions to gelatine have been reported. Allergy to gelatine is a common cause of an allergic reaction to vaccines, many of which contain porcine (pig) gelatine as a stabiliser. If you have experienced symptoms of an allergic reaction after eating gelatine, talk to your healthcare provider before getting vaccinated.

- Seed: Allergic reactions to seeds can be severe. Sunflower and poppy seeds have been known to cause anaphylaxis.Seeds are often used in bakery and bread products, and extracts of some seeds have been found in hair care products.Some seed oils are highly refined, a process that removes the allergy-causing proteins from the oil. But as not all seed oils are highly refined, individuals with a seed allergy should be careful when eating foods prepared with seed oils.

- Spice: Allergies to spices, such as coriander, garlic and mustard, are rare. These allergic reactions to spices are usually mild, although severe reactions have been reported. Some spices cross-react with mugwort and birch pollen. People who are sensitive to these environmental allergens are at a higher risk for developing a spice allergy.

- Fruit and Vegetables: Allergic reactions to fresh fruits and vegetables—such as apple, carrot, peach, plum, tomato and banana—are often diagnosed as Oral Allergy Syndrome.

CROSS REACTIVITY

Individuals who exhibit reactions to specific food allergens, inhalants, or substances may develop allergies to others due to a phenomenon known as allergic cross-reactivity. This occurs when the body reacts to different foods containing the same allergen or substances with similar protein structures. Allergic reactions resulting from cross-reactivity can range from mild to severe.

This means that someone may suffer an allergic reaction even when avoiding the foods they know they are allergic to. For instance, if someone is allergic to peanuts, they may also experience reactions to foods like soy, peas, lentils, or beans, as they belong to the same biological family (legume). Another example can be when it comes to an allergy to ragweed, you may also develop reactions to bananas or melons. Allergic cross-reactions can also occur between certain fruits or vegetables and latex, a condition known as latex-food syndrome, or with pollens that trigger hay fever.

In cases where an individual has a diagnosed reaction to a specific food, avoiding similar foods that could potentially trigger a similar reaction may be advisable. However, it’s important to note that while certain cross-reactivities, such as between apples and birch pollen, are well-documented, not everyone allergic to one substance will necessarily react to others. Therefore, assumptions about cross-reactivity should be avoided, and important foods should not be eliminated from the diet without proper testing and clinical assessment.

FINDING HOPE

What sodding difference does the underlying mechanism make if foods are still making me feel so awful, I hear you cry. And I get it. So, in severe cases the difference ultimately could be the difference between life and death. And a food allergy, which could get worse or unexpectedly escalate in brutality requires an equally heavyweight Epipen response. Whilst there is a chance of growing out of allergies after childhood, many don’t. Knowing where you are with something so serious, and being able to plot life accordingly is vital.

On the flip side, when it comes to the other immunological and non-immunological reactions, knowing the difference can give you clarity and hope on which debilitating responses and symptoms you have an opportunity to change. There are a multitude of options available for dealing with enzyme deficiencies, reducing histamine load and working with oxalates as well as modulating and calming an immune system that later builds tolerance to offending foods.

For anyone researching allergies, immune mechanisms and the rise in increasingly poor health across multiple populations and conditions, the evidence is clear- western diets, food processing, environmental toxins and increased mental and physical stress are key players and a gateway in triggering immune responses with food. Creating a life that addresses these issues and creates space away from them is a great place to start any line of education and healing for immune health.

ACHIEVING IMMINE BALANCE

It’s important to bear in mind that whilst some people may have a very clear-cut allergy to a single allergen and nothing else, many suffer from a multitude and mixture of both immunological and non-immunological reactions that can all be taking place at once. Our immune system is a dynamic ever evolving systems where the interplay between us and our environments is constantly in flux.

Regardless, there is a way to manage even the toughest of immune system set ups. With thorough testing, expert insight, steely determination, helpful strategies and well thought out protocols it is possible to holistically manage, untangle and ultimately soothe whatever convoluted set of symptoms and triggers you face.

METHODS OF MANAGEMENT

Managing allergies, sensitivities, and intolerances can involve a combination of conventional medicine, complimentary support and a holistic, integrative approach. Many individuals benefit the most from a carefully curated methodology drawing on the best that each field has to offer. Complete avoidance is often necessary in all adverse food reactions at least initially, with IgE responses and Coeliac demanding a lifelong abstention to avoid potentially life defining repercussions. Sensitivities can often be worked through and modulated with targeted protocols that facilitate the calming and retraining of the immune system. Metabolic driven ones can frequently be supported and mediated with the use of enzymes support.

ALLOPATHIC APPROACHES:

Medications:

- Antihistamines: Commonly used to relieve symptoms such as itching, sneezing, and runny nose in allergic reactions.

- Corticosteroids: These anti-inflammatory drugs help reduce inflammation and alleviate symptoms in more severe allergic reactions.

- Epinephrine (adrenaline) injectors: Essential for individuals with severe allergies (anaphylaxis) to quickly reverse life-threatening symptoms.

Allergen Avoidance:

- Identifying and avoiding allergens that trigger allergic reactions is a key component of managing allergies.

- This may involve reading food labels, implementing environmental controls (e.g., using air filters, avoiding pollen exposure), and avoiding known triggers.

Allergen Immunotherapy:

- Allergy shots (subcutaneous immunotherapy) or oral immunotherapy may be recommended for individuals with severe allergies.

- These treatments involve gradually exposing the individual to increasing amounts of allergens to desensitise the immune system and reduce allergic reactions over time.

HOLISTIC APPROACHES:

Dietary Modifications:

- Elimination Diet: Identifying and removing trigger foods from the diet can help manage food sensitivities and intolerances.

- Rotation Diet: Rotating foods to prevent overexposure to specific allergens and reduce the likelihood of developing new sensitivities.

- Gut Healing Protocol: Focusing on gut health through probiotics, prebiotics, and gut-healing nutrients to strengthen the digestive system and reduce food sensitivities.

Nutritional Supplements:

- Certain supplements, such as quercetin (a natural antihistamine), vitamin C, and omega-3 fatty acids, may help reduce inflammation and support immune function.

- Digestive Enzymes: Supplementing with enzymes may aid in the digestion of certain foods, alleviating symptoms of intolerance.

Stress Management

- Stress reduction techniques such as mindfulness, meditation, yoga, and deep breathing exercises can help modulate the immune response and reduce the severity of allergic reactions.

Traditional Medicine Practices

- Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Ayurveda, and herbal medicine offer various approaches to managing allergies and intolerances, focusing on restoring balance and harmony within the body.

- Acupuncture and acupressure may also be used to alleviate symptoms and support overall health.

Environmental Modifications

- Natural remedies for environmental allergies may include using saline nasal sprays, steam inhalation, and herbal teas with anti-inflammatory properties.

INTEGRATIVE APPROACH

Working with a healthcare provider who is knowledgeable about both approaches can help develop a personalised treatment plan tailored to individual needs. Discussing allopathic approaches such as avoidance and medication are vital, as are the holistic ones such as dietary modifications and gut health optimisation.

Creating collaboration between conventional and alternative methods (an irritating terminology to be discussed another day) supports healthcare practitioners to achieve improved outcomes. And aids better management for those who suffer allergies, sensitivities, and intolerances. Navigating a path that addresses symptoms and improves wellbeing, often to the point of perceived cure.

WHEN TO CONSULT AN ALLERGY SPECIALIST

The importance of professional guidance in managing allergies and intolerances must be emphasised. The risk of an inappropriate approach to the correct identification of immune reactions can lead to inappropriate diets with severe nutritional deficiencies. All unclear diagnoses, especially those with severe reactions warrant expedited action. Even away from extreme and potentially life threatening symptoms, far too often plenty of people who have lived with and ultimately normalised clear and certainly life blighting immune reactions that could easily be moved past with the help of professional direction and insight. I urge anyone who finds their body communicating an issue with food to take the time to get to the bottom of it, if only to live a life free from the discomfort sooner rather than later.

CONCLUSION

Both allergies and intolerances can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life, affecting dietary choices, social interactions, and the overall well-being of both the individual and immediate family. Whilst they share some similarities in their symptoms, causes and dietary restrictions, they are fundamentally different conditions with distinct underlying mechanisms

In the intricate tapestry of human health, and due to the central role our immune systems play, understanding these differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis, effective management, and improved quality of life. Whether you’re navigating your own severe allergies, nuanced symptoms and dietary restrictions or supporting someone else and interested in a defining conversation of our age, knowledge about allergies and intolerances empowers everyone to make informed decisions and promote better health outcomes.

This post draws on multiple sources of scientific research. Should you wish to know more about the individual papers and information, or recieve a list of the full references post, please contact me directly.

A fan of people, plants, leisurely feasts and a good brew, she runs clinics, workshops, women’s circles and wellbeing retreats alongside developing bespoke lifestyle plans for people with complex allergy needs.

Sophie is a certified and registered multi-disciplinary practitioner specialising in the field of immune health and allergy.

© 2021- A Modern Topic

Come connect, share, and learn gently.

For curious minds and open perspectives.

@amoderntopic

Site credit